History is all around us, the past leaves footprints everywhere.

You wouldn’t know it to look at them, but the stretches of farmland in Northamptonshire, a county which has long been prone to rebellion, were once almost battlegrounds of resistance…

The Swing Movement

When the fields of southern and eastern England were swaying in the winds of anger in the winter of 1830, Northamptonshire was not immune. The county’s hedgerows and high streets became part of a wider wave of rural protest we now call the Captain Swing riots – a movement of farm labourers, craftsmen, and their families who were squeezed by low wages, poor harvests, and the spread of labour-saving (or job-taking) threshing machines.

By 1830, winter work that had once kept men paid, hand-threshing, had been undercut by horse-driven machines. This was the process of removing edible grains from the straw and husks of a plant, traditionally done by hand with tools like a flail.

Wages had slipped; parish relief was threadbare; but rent day still came on time.

In this climate, crowds across the country gathered at dusk, visited farms, bargained hard, broke the odd machine, drank a landlord’s beer, and moved on.

Most violence was against property; most demands were practical: more pay, no machines.

Parish by parish, those letters warned farmers to smash their machines, raise wages, or face the consequences.

Letters from “Captain Swing” ?

The movement’s most famous calling card were letters: blunt, misspelt, and menacing, signed with a name no constable could arrest – “Captain Swing.”

Northamptonshire saw its share of Swing letters. They were often delivered at night to clergy, overseers, and well-to-do farmers. A typical note threatened that unless the “engins” were taken down and wages advanced by Monday, “we will Swing you up.”

Local magistrates read them with mounting alarm. Special constables were sworn in. The Northamptonshire Yeomanry was placed on call.

And when arrests followed, something else stirred: support for the movement.

On the road

One of the most striking Northants episodes belongs not to a farmyard, but to the highway. As constables and parish officers began marching or carting prisoners to the county gaol (jail) at Northampton, crowds gathered near Wellingborough to stop them.

A contemporary report describes an escort carrying men taken at or near Oundle and Warmington heading toward Northampton. One of these men was the notorious Swing agitator, Thomas Marriott. He had travelled from nearby Huntingdonshire, representing some of the many roving protesters, who would follow the action to support fellow Swingers.

Word spread ahead of them. In Wellingborough, townsfolk and country people met the party, halted the procession, and interfered with the removal – variously by sheer weight of numbers, by shouting down the officers, and by the rough-and-ready moral authority of the street. The aim was simple: prevent their neighbours being swallowed by the gaol.

Following the rescue of at least two of the prisoners, an effigy of the Prime Minster, Arthur Wellesley, was brandished around the town and finally burned.

Something similar flared again after arrests in Finedon. As men seized there were being conveyed away, people turned out to challenge the escort, echoing the earlier Wellingborough stand. Whether the prisoners were prised free, turned back, or only delayed depended on the day and the balance of nerve; but the message was unmistakable: processions to prison would not go uncontested.

These highway confrontations mattered. They showed that Swing in Northamptonshire wasn’t only about wrecking machines in a distant stackyard. It was also about community defence – neighbours standing between arrested men and the lock-and-key of Northampton gaol.

Who were “The Crowd” ?

Unlike roving rioters like Thomas Marriott, the crowd was not a hired mob from elsewhere, but locals: labourers and shoemakers; lacemakers and smiths; lads who could run messages along the turnpike; older women who knew who had been taken and why.

Wellingborough’s market town web – trades, chapels, alehouses, kin – helped gather people quickly. The same social glue held in Finedon, Irthlingborough, and the villages strung along the Nene.

Here thee, hear thee

One of those arrested in Finedon was Philip Desborough, the town crier. He was accused of inciting a riot for crying that no labourer was to go to work the next morning, without having 2s.3d a day; many Northamptonshire labourers at the time were actually getting 1s.6d. to 2s per day, and sometimes less in slack months.

Meanwhile, records show that Parish Relief gave a weekly allowance for a man, wife, and two children at around 9s. to 10s. a week – that works out as the equivalent of about 1s.6d. to 1s.8d. per person, per day, without the uncertainty of whether you’d find farm work.

When Philip Desborough shouted that no man should work for less than 2s.3p a day, he wasn’t asking for luxury – he was asking for work to be worth more than the Parish dole. At the time, Poor Relief for a family could match or even beat farm wages. Desborough’s demand was really a call for dignity: to make labour pay better than charity.

What did this show?

Those Wellingborough interceptions widen the usual picture; Swing wasn’t only a “machine-breaking riot” – it was also a battle over process: who decides wages, who polices the parish, who may be carried off to prison without the neighbourhood having its say.

Stopping the cart to Northampton, even for an hour, turned a private arrest into a public negotiation. It put the moral economy of the community, their sense of fair play and survival, against the letter of the law.

For just a season in 1830–31, that argument played out in barns and byres, but also in the middle of the road, with Wellingborough and its neighbours as a stage.

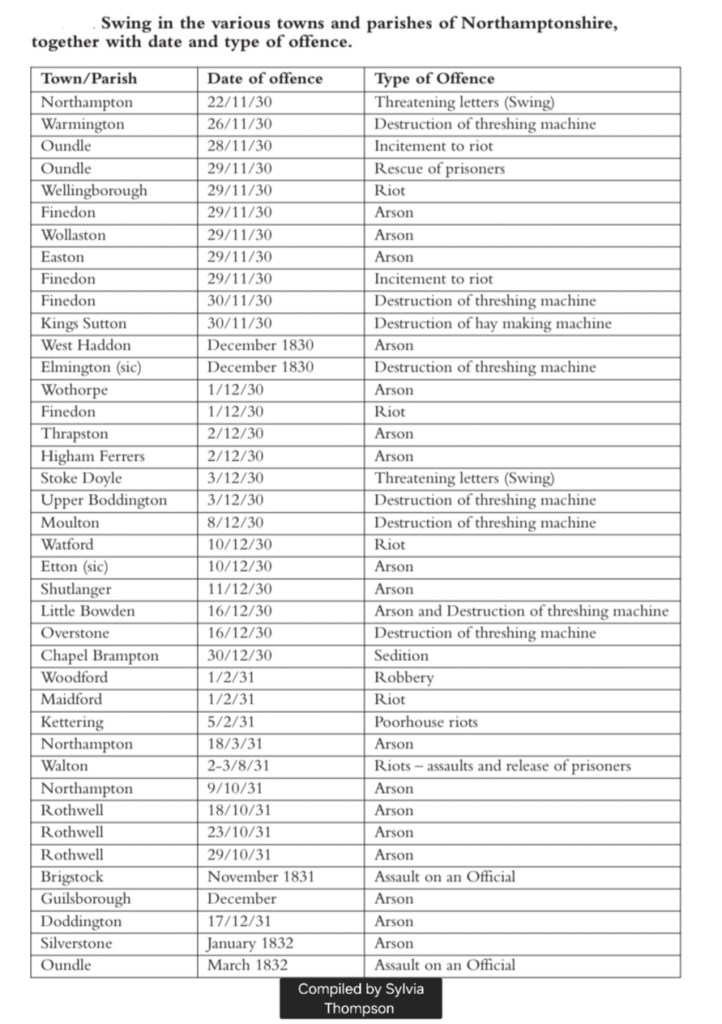

Swing offences in Northamptonshire

How did the authorities respond?

Magistrates treated interference with escorts as a direct challenge. Charges like riot, rescuing prisoners, assault on a constable, and unlawful assembly followed. Courts leaned hard: some men were imprisoned; others transported.

The county also strengthened patrols on the roads and leaned on innkeepers not to harbour “disturbers.”

And yet…

In the House of Lords, Earl Grey suggested that reforms should be introduced in the House of Commons. But Prime Minister Wellesley shot this down, claiming that the current constitution was so perfect that any changes would be a downgrade. In response, his London home was attacked by Swing rioters.

A couple of days later, his government was overturned, and Grey was asked to form a Whig (later known as the Liberals) Parliament.

Sources

Great Addington History, “The Georgians”

Northampton Museum and Art Gallery, “Northamptonshire Yeomanry”

Carolyn Smith, “Researching the Finedon Swing Riots of 1830”, Finedon Local History Society Newsletter of May 2018

Sylvia Thompson, “On the Verge of Civil War:The Swing Riots 1830-1832”, Northamptonshire Past and Present Number 64

The Workhouse: Story of an Institution, “The Speenhamland System”