Long before Hogwarts (and even Harry Potter House) there was Thomas Fysh of Kettering – dragged before the dreaded Star Chamber for possessing what sounds like a wizard’s notebook.

His crimes? Owning “a book of Coverdale’s making” (almost certainly one of the earliest printed English Bibles) and keeping “a paper drawen with fygures and circulls moche lyke to conjuracions.”

To Tudor officials, both items were dangerous. The first was heretical: English Bibles were illegal under Henry VIII before 1538. The second was suspiciously magical: circles and symbols looked like sorcery to the untrained eye. Together, they painted a picture of a man meddling in both forbidden religion and forbidden arts.

But Fysh’s story isn’t an isolated oddity; it fits right into Northamptonshire’s surprisingly radical role in early English reform. This part of the Midlands had long been a quiet hotbed of religious dissent by the Sixteenth Century.

The Lollards

Long before Henry VIII’s break from Rome, a group of ordinary English people were already challenging the Church’s power. They were called Lollards, followers of the rogue Oxford scholar John Wycliffe, who lived in the late 1300s.

Wycliffe believed that everyone, not just priests, should be able to read the Bible in their own language. Latin, he said, should not be the barrier between ordinary people and God.

At a time when Scripture was only in Latin, this was a daring idea. His supporters secretly translated the Bible into English and copied it by hand, passing it from reader to reader.

Wycliffe’s ideas spread like wildfire across the Midlands – especially along the route from Oxford to Leicester, through Northampton.

By the early 1400s, Northamptonshire had become one of the movement’s strongholds. People met in barns, cottages, and even fields to read from hand-copied English Bibles, risking arrest for “possessing heretical books.”

These books were usually Wycliffe translations: handwritten copies of the English Bible made secretly by believers. Each was precious, often passed from hand to hand across the county. Reading one aloud could gather a small crowd, and copying one by candlelight could take months.

Bishop after bishop complained about “heretics” in these parts, caught with “bokes of Scripture in Englysshe.”

But still they read. In towns across the county, ordinary folk met in barns and back rooms to hear the Bible spoken in their own tongue. One would read, another would listen, a third would make a new copy by flickering light.

Some thought that authorities in the county actively encouraged Lollardy. A petition was raised against the Mayor of Northampton, stating that he all but authorised Lollard meetings, and that he actively harboured prominent people in the movement.

The complaint was raised, but seemingly fizzled out, as there is no evidence he faced any punishment; was the local Lollard movement so strong, that the Mayor could almost shrug off such an accusation, and keep his Chain of Office?

By the time Henry VIII came along, the Lollards had been hunted for over a century… but they hadn’t gone. Beneath the surface, the old network still whispered and read.

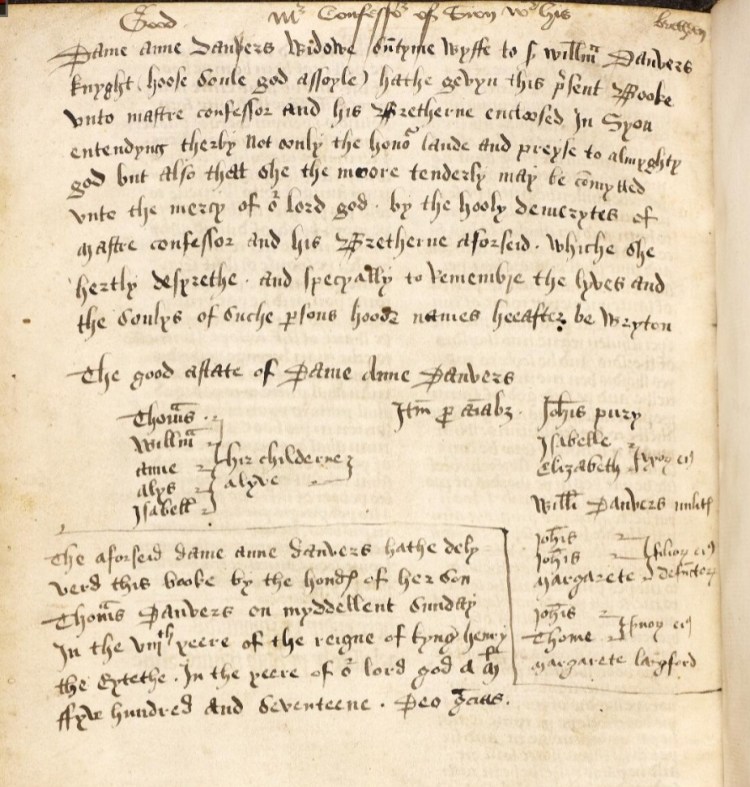

We even know of one Northamptonshire woman, Dame Anne Danvers of Culworth (near Sulgrave), who owned an English New Testament and donated it to Syon Abbey in 1517.

Imagine that: a gentry lady quietly doing what thousands of “heretics” had been punished for doing generations before. Times were changing.

–

Miles Coverdale was a later Bible translator, who produced the first full English edition

So when the Star Chamber accused Thomas Fysh of owning “a book of Coverdale’s making,” it wasn’t witchcraft they’d truly sniffed out; it was literacy.

The circles and symbols they called “conjurations” might have been notes, diagrams, bored doodling, or even shorthand for Bible study.

In truth, Thomas Fysh (probably) wasn’t a conjuror; he was one of Northamptonshire’s earliest heretics of the printed word, a man whose “magic” was simply the ability to read forbidden English.

Sources

Stephen Alsford, Town authorities accused of abetting Lollardy

Frederick Bull, History of Kettering, archived by Northamptonshire Records Society

Northamptonshire Battlefields Society, The Lollards

Francis Macnamara Nottidge, Memorials of the Danvers Family