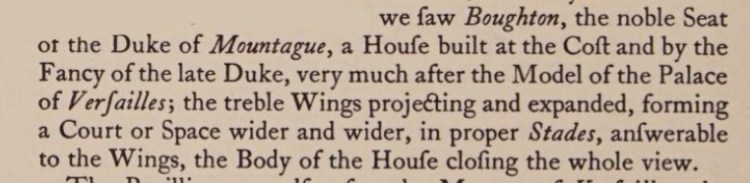

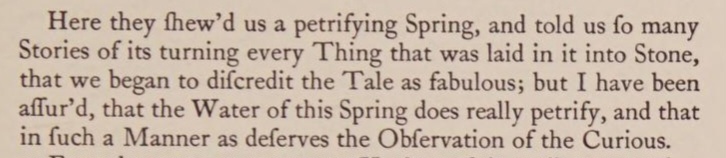

During his travels across Britain, writer Daniel Defoe stopped by Boughton House. His hosts showed him a spring which they insisted would “petrify” anything left within its water, or turn it to stone.

Defoe dismissed this as fantasy, or perhaps thought it was a joke at his expense. Either way, his passing comment was that the matter “deserves the observation of the curious.”

And he was right…

Side note: Defoe skims over an important point – the spring was in Boughton Park near the village of Boughton; not in the grounds or estate of Boughton House; they are several miles apart. I wasn’t able to find any familial connection between the Wentworths of Boughton Hall, and the Montagus of Boughton House. It seems that Defoe’s hosts wanted to show him a fairly local curiosity, and the name-similarity is just a coincidence.

Curiosity Springs Eternal

Petrifying springs were highly fashionable in the 17th and 18th centuries. They sat neatly at the crossroads of science, superstition, and spectacle; exactly the sort of “natural wonder” that filled cabinets of curiosity and drew the attention of scholars, nobles, and royalty.

At Boughton, the spring rose naturally at the edge of the park, later enclosed beneath a stone grotto. Local tradition and writers record it as a spring that would “turn wood into stone” … more accurately, one that encrusted objects with a hard mineral crust, giving the appearance of petrification.

The spring almost certainly predates the surviving grotto. Although the stone structure is generally dated to around the 1770s, built during the landscaping works of William Wentworth, there are strong indications that the spring itself was already well known long before then…

A Royal Visit

During his imprisonment at the nearby Holdenby House in 1647, Charles I was allowed limited excursions under guard.

According to local legend, Charles would use the grotto’s predecessor, possibly a pagan site, as a changing room before bathing in the spring’s water.

Charles had probably heard of this spring, at least in passing. He had an interest in such curiosities, and sometime previous had examined a skull which was partly coated in limestone, similar to objects left in a petrifying spring.

He may well have asked for the use of Boughton Spring once he had been taken to Holdenby.

How Do They Work?

Despite the folklore, petrifying springs were not magical. They were chemical.

Such springs are rich in dissolved calcium carbonate, picked up as rainwater passes through limestone or ironstone underground. When the water emerges into open air, carbon dioxide escapes, and the dissolved minerals are deposited as a solid crust.

Over time, this crust builds up on whatever is left in the water. The object inside eventually decays, leaving behind a hollow, stone-like shell. The process does not replace the object: it coats it.

At strong springs, early visible encrustation can occur in months. Thick, durable coatings usually take years.

Springs like Boughton’s would once have been able to produce impressive results within a human lifetime, which is why they fascinated early observers.

Now

Today, the Petrifying Spring of Boughton has been closed off from the public. But the grotto remains, Grade II listed, a quiet reminder that this small spinney once hosted a phenomenon curious enough to attract scholars, antiquarians, and even a king.

Sources

Boughton Parish Council (2016) Boughton Village Design Statement.

Heritage England (2004) Grotto at Grotto Spinney.

Holy and Healing Wells (2016) A Northamptonshire field trip – the holy and ancient wells of Boughton.

Northamptonshire’s Historic Environment Record (2022) Listed Building: Grotto at Grotto Spinney

University of Cambridge (2024) The Candia Skull: from Minoan Crete to 17th-century Cambridge.