Kettering’s worsted wool industry had a classic rise and fall: born from local resources and skill, reaching a peak of prosperity that shaped the community, then declining in the face of innovation and global change.

It is a story shared by many towns of England’s bygone “woollen districts”, but with its own distinctly local flavour. For the people of Kettering, the wool trade was once the warp and weft of daily existence – an era when “Industry” was not a business park or cluster of warehouses on the edge of town, but the clack of your neighbour’s loom heard through the wall.

And though that era has passed, its legacy is woven into the history of the town, a rich tapestry of hard work, adaptation, and community spirit.

Enclosure

By the Middle Ages the town was already a small market centre surrounded by sheep-grazing countryside. However, it wasn’t until the mid-1600s that weaving in Kettering truly expanded from a homespun craft into a real industry – and ironically, it was the Inclosure System that helped it to grow.

Enclosure of pasture land had improved local sheep breeds, producing a high-quality long-staple wool perfect for making worsted cloth – worsted yarn is spun from long, combed fibers, yielding a strong, smooth thread ideal for fine textiles.

This advantageous wool supply did not go unnoticed. Enterprising locals began to organise production: wool was bought from nearby farmers, sorted, and “put out” to villagers to spin and weave for payment.

What had been a modest household chore was turning into a thriving cottage industry.

Worsted Wool

In the late 17th and 18th centuries, Kettering became one of Northamptonshire’s leading centres for the worsted wool trade, with whole families spinning and weaving in their cottages. At its height, the town was sending hundreds of pieces of cloth a week to London, and the rhythm of the loom was part of daily life in almost every street.

It was made from the longest, smoothest fibres of the fleece, which are carefully combed straight and parallel before spinning. This makes the yarn strong, fine, and smooth, quite different from the softer, fluffier “woollen” yarn spun from shorter fibres.

The result? Durable, high-quality cloth that could be made into serge, shalloon, tammy, and other fabrics. It kept a sharp crease, wore well, and was much in demand for linings, uniforms, and fashionable clothing.

Shalloon

Shalloon was a lightweight worsted fabric, made from those smooth, combed long-staple wool fibres. It was usually thin, strong, and tightly woven, mainly used for lining coats, gowns, and uniforms.

Kettering became especially known for making shalloon in the 18th century. Contemporary reports say that by the 1740s the town was sending as many as 1,000 pieces of shalloon a week to London. That trade helped make Kettering one of Northamptonshire’s most important worsted centres during its peak years.

Tenters

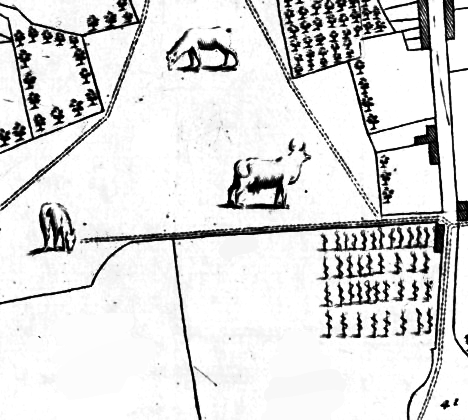

The 1721 Map of Kettering shows four rows of tenters in what is now Commercial Street carpark, near Wadcroft – these were frames onto which woven cloths were stretched to be bleached and shrunk in the open air.

The end looms …

Things started to unravel as industrialisation spun on. Inventions such as the Spinning Jenny (1764), Arkwright’s water frame (1769), and later the power loom turned out yarn and cloth faster and cheaper than hand-spinners and hand-weavers in Kettering ever could.

By the late 18th century, even Northamptonshire’s best fleece was often sold north to feed Yorkshire’s mills, instead of being worked locally.

By 1794, the workforce of spinners, combers, and weavers in Kettering had halved — falling from around 6000 people to barely 3000. Apprenticeship contracts that once bound young boys to master weavers all but disappear from the records after this point.

Global factors also played their role – the Napoleonic Wars hit hard. Overseas markets for English woollens shrank, and continental trade routes were blocked.

For a localised industry like Kettering’s, already weakened by competition, this was a crushing blow. A report from 1817 records just over 1000 residents on parish relief, and by 1821 more than half of Kettering’s population were classed as paupers. The unravelling of the worsted trade was at the heart of this social crisis.

By the mid 1820s, Kettering’s worsted wool industry was effectively dead. A few elderly craftsmen may have kept their looms going out of habit, but as an economic force it was gone.

Across England, industrialisation was met with protests. Next week we’ll look at such movements in Northamptonshire…

The Benfords

One particularly prominent family in Kettering’s Wool Industry was the Benfords, who had at least two generations of “Ben Benford”. Their business seemed to survive at least partway into the mechanisation of the industry.

How did Wadcroft get its name?

Wad = an old Northamptonshire dialect for “woad”, a plant grown to make blue dye;

Croft = an area of land.

Woad was used to dye fabrics, and it is thought to have once been used to paint the skin of Celtic tribes.

Sources

Genealogist Goes Wandering

Kettering Cultural Consortium

Northamptonshire Industrial Archaeology Group

Sugden, Keith (2011)

I knew Kettering once had a woollen industry but had no ide how important it was. Thank you

LikeLike